Jasmina Cibic: The Gift Ecology

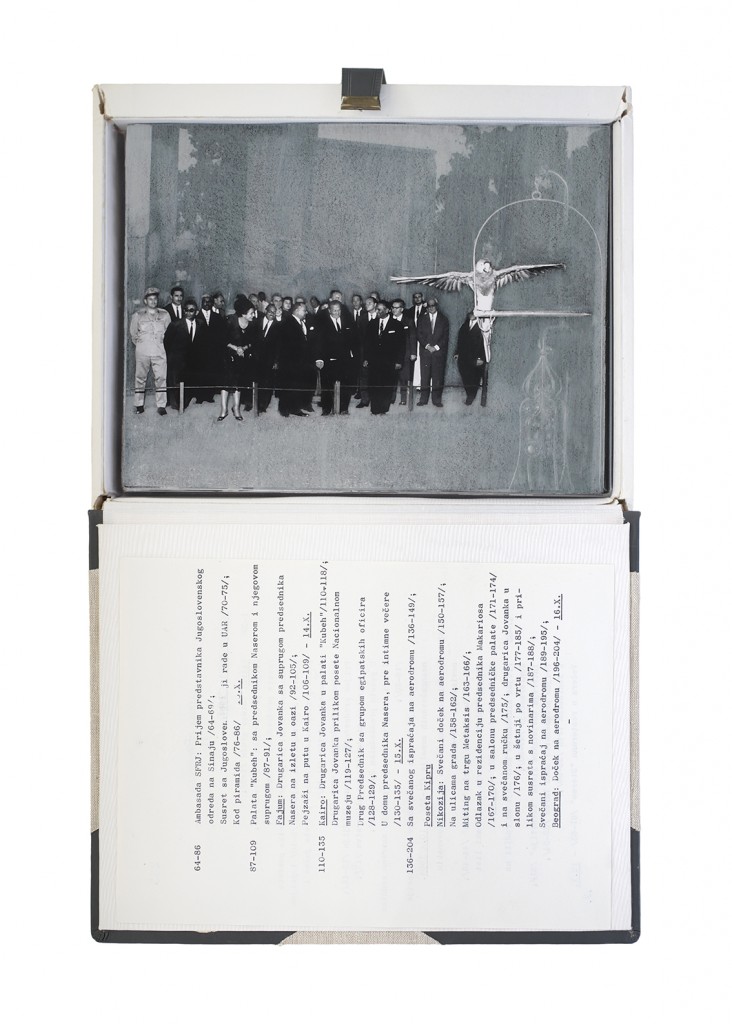

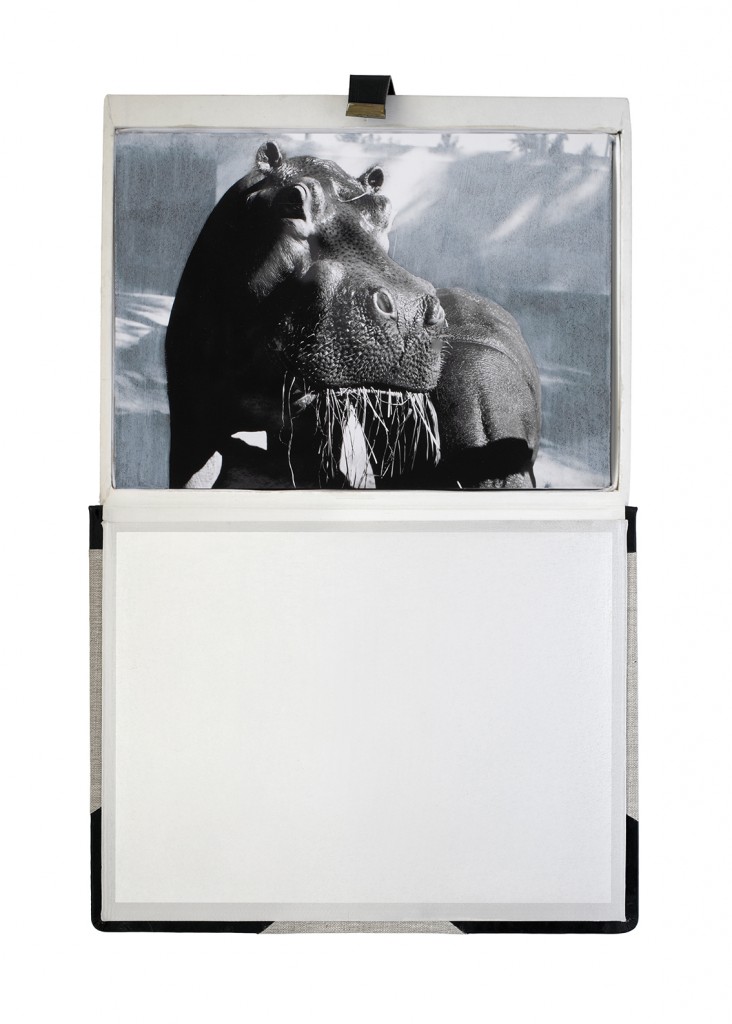

The exchange of animals and plants as diplomatic gifts traces back to the origins of patriarchal authority, serving as markers of geopolitical influence and cultural prestige. In modern times, the ultimate emblem of territorial conquest and colonial ambition became the zoo, which not only showcased global power but also demonstrated the supposed capacity of Western civilisation to control nature and impose an enlightened order.

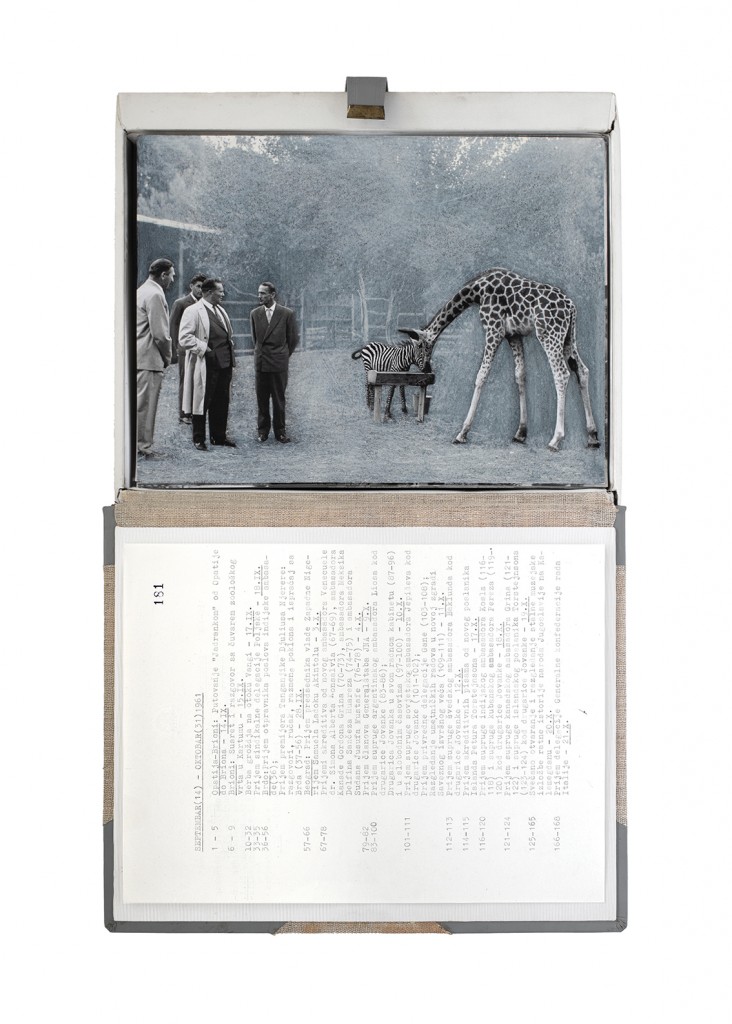

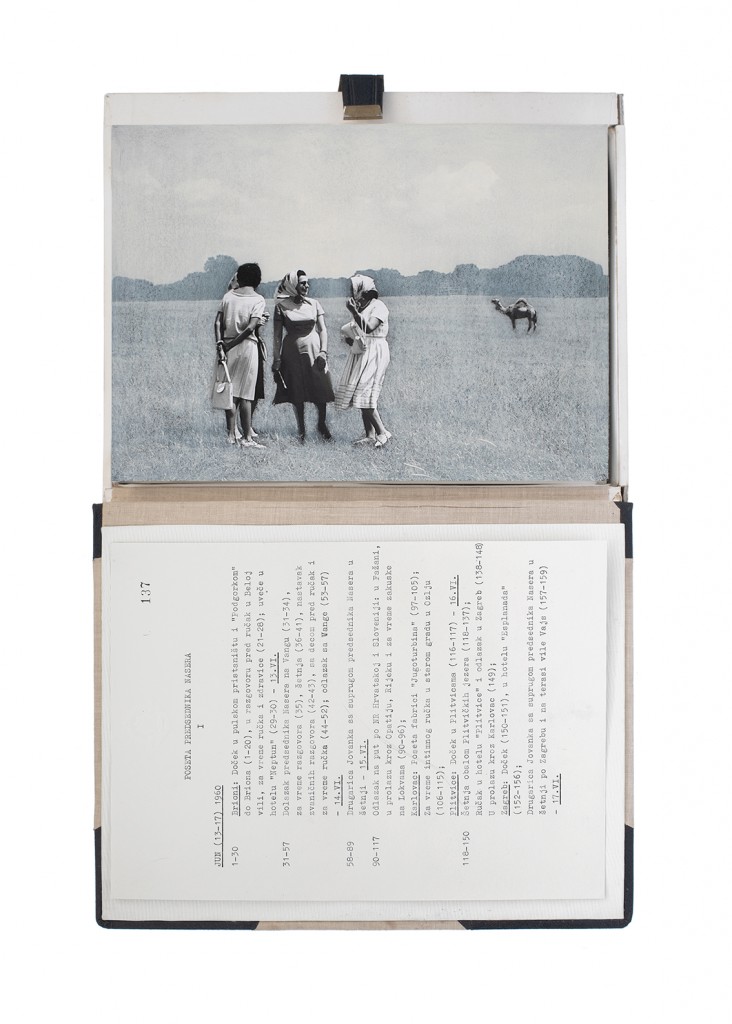

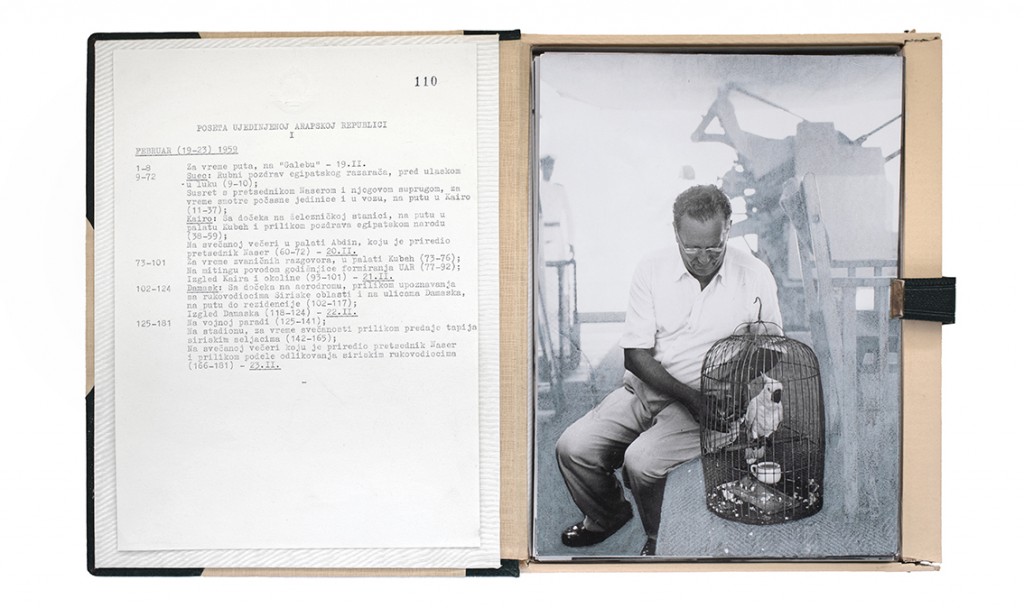

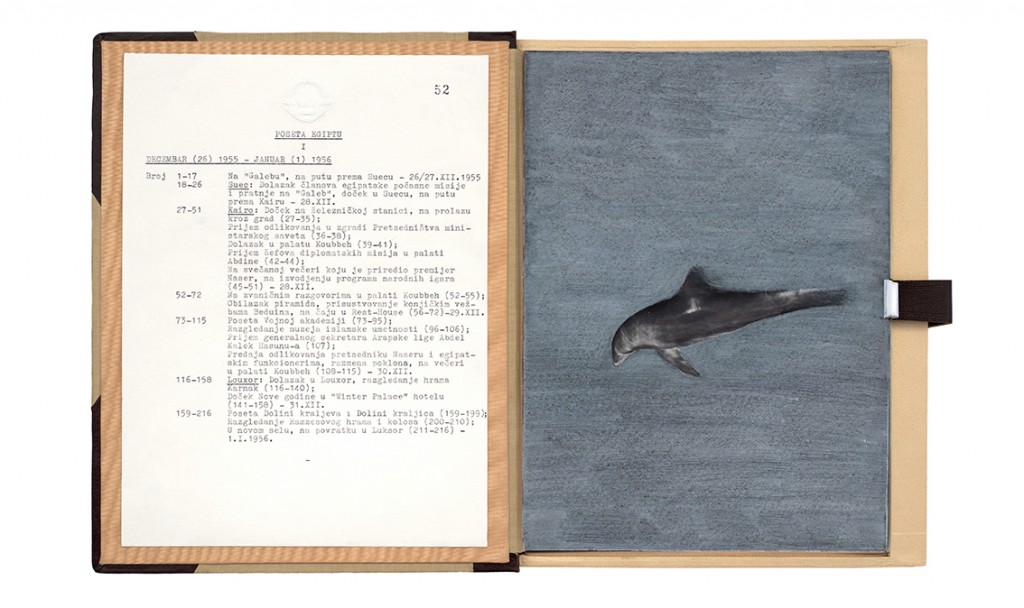

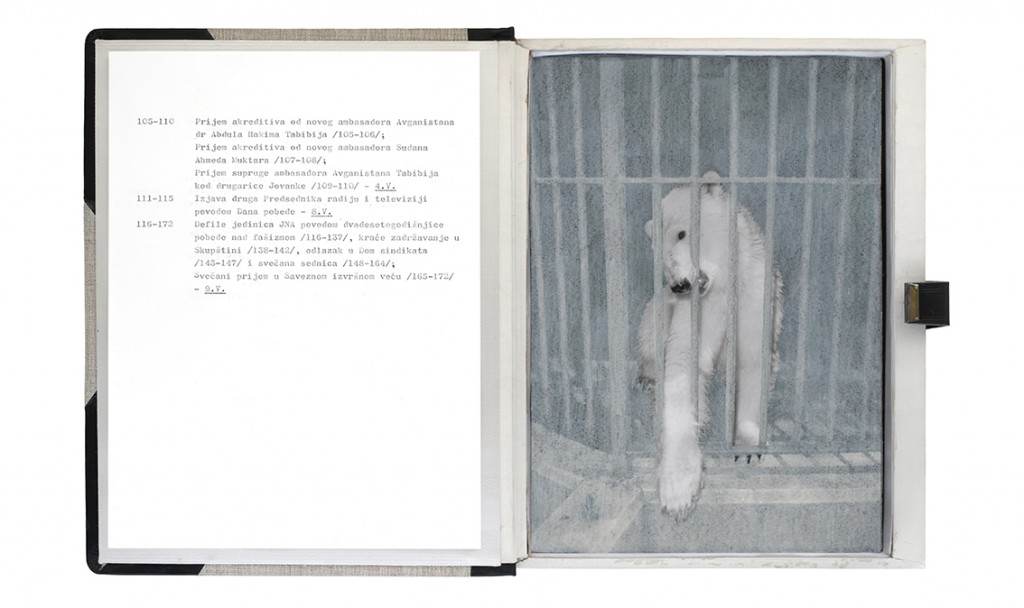

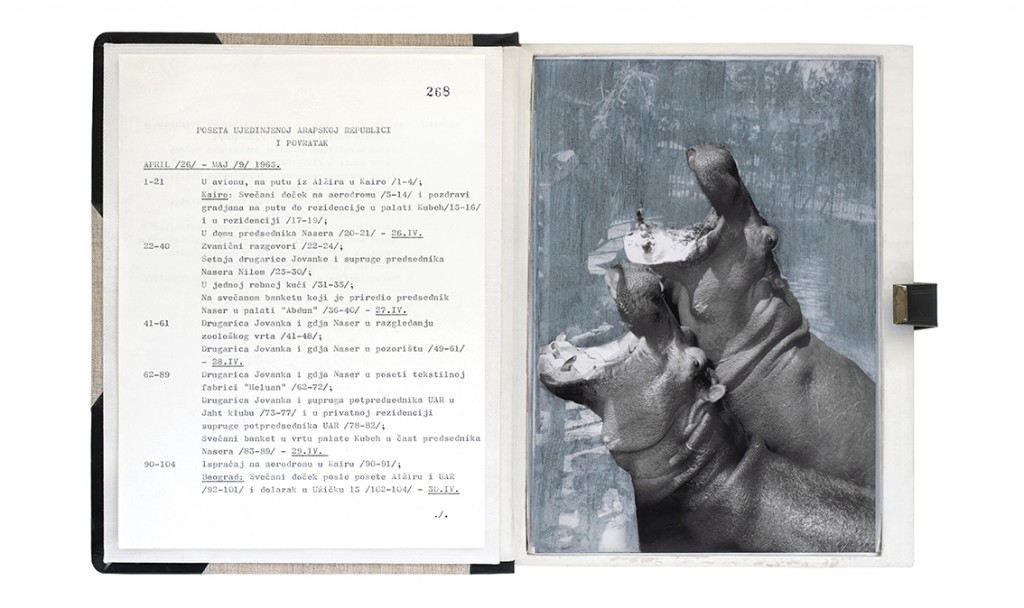

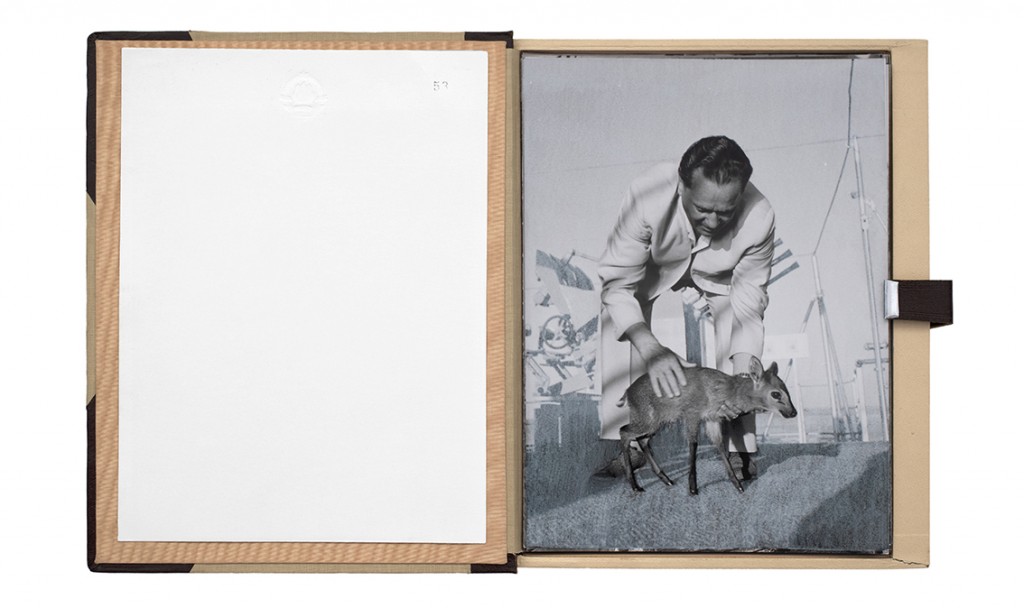

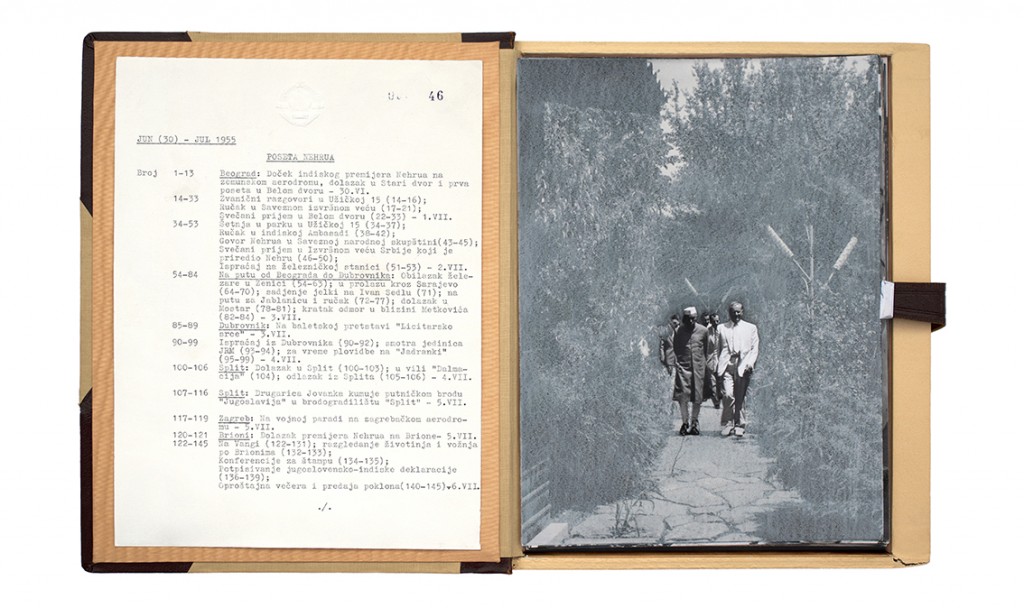

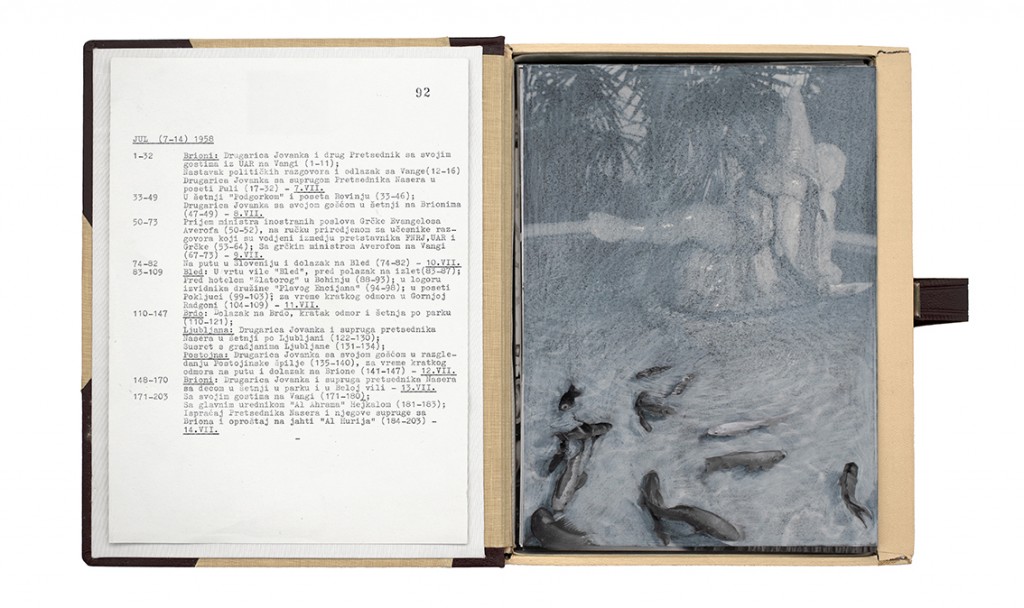

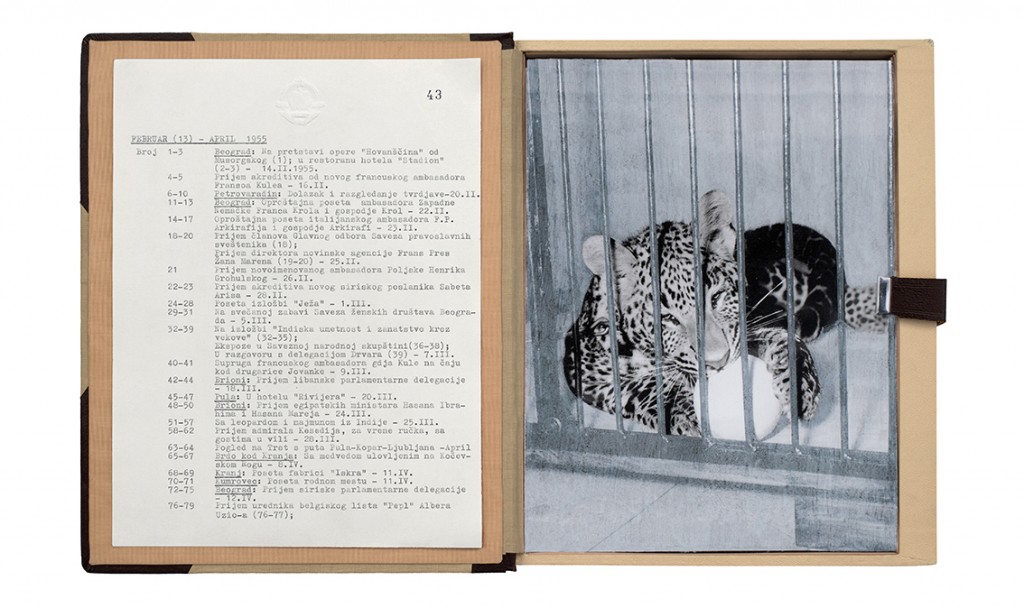

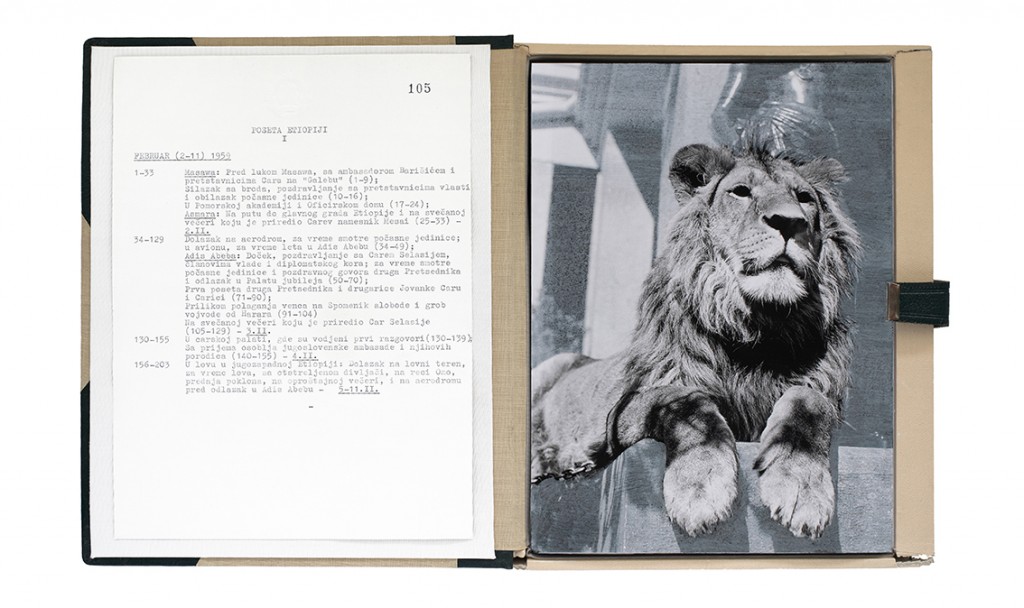

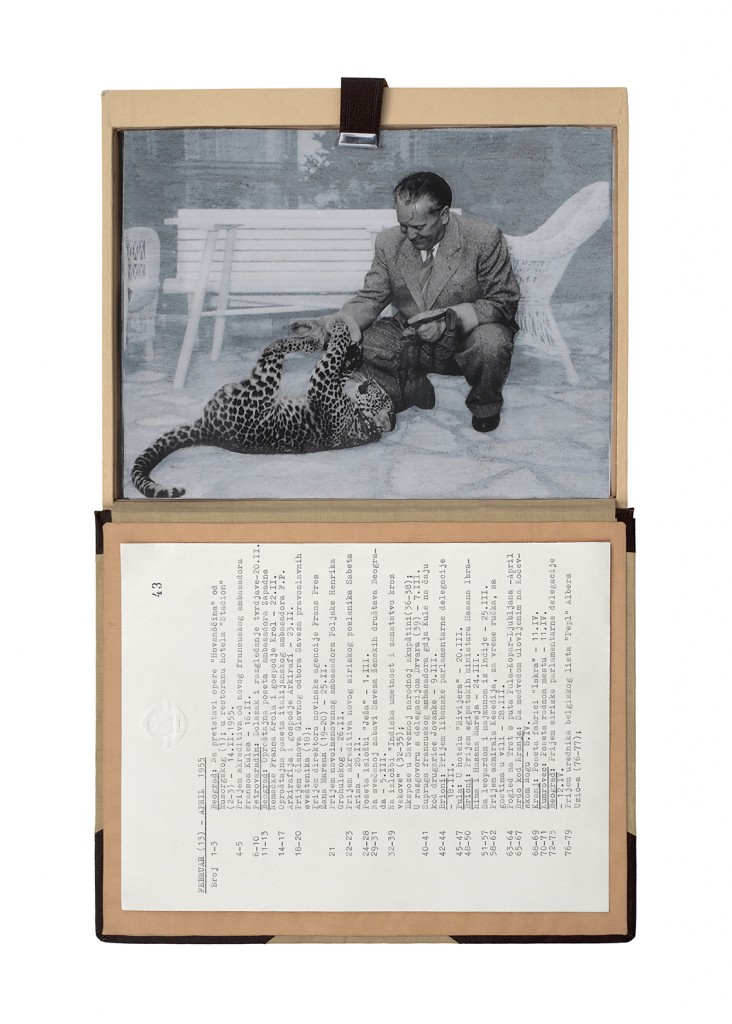

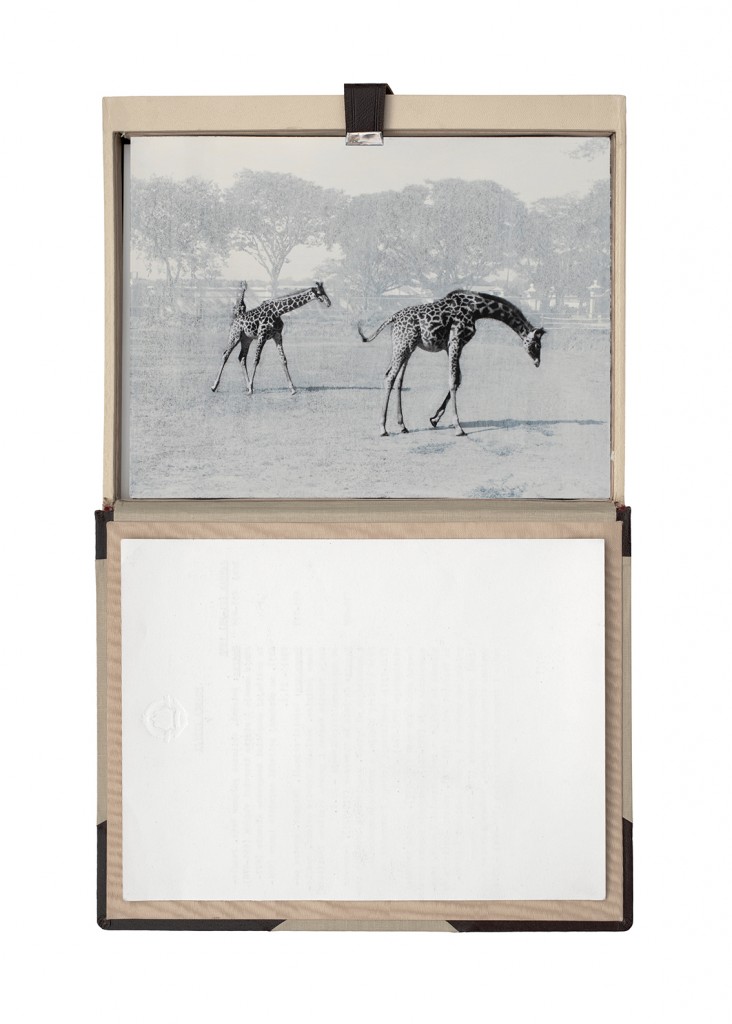

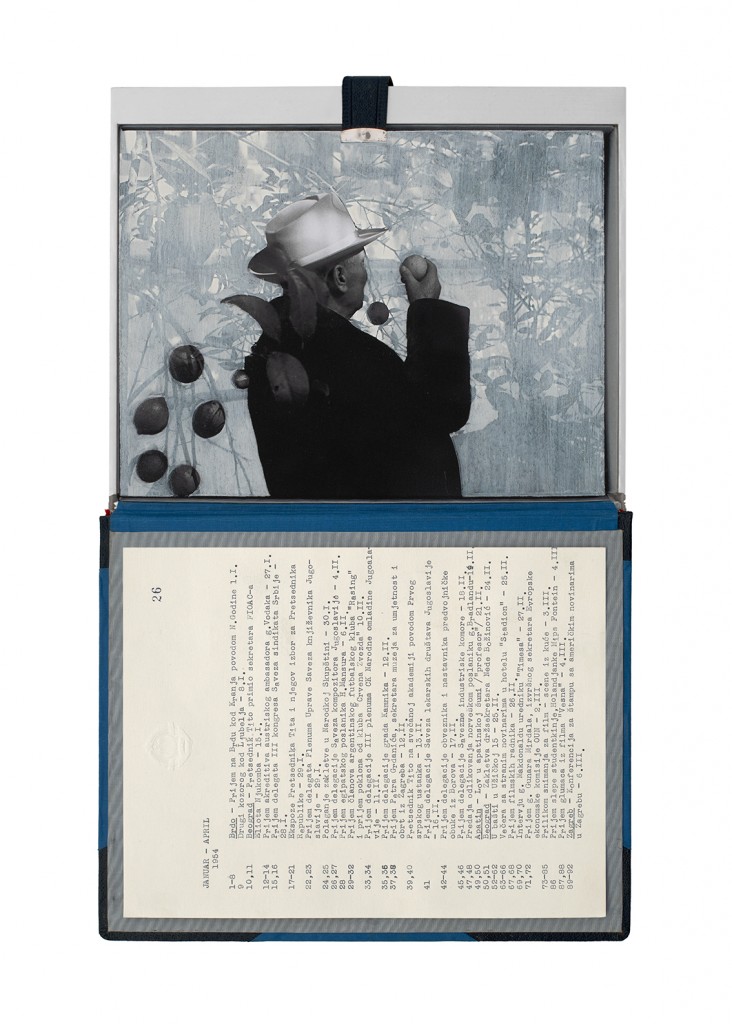

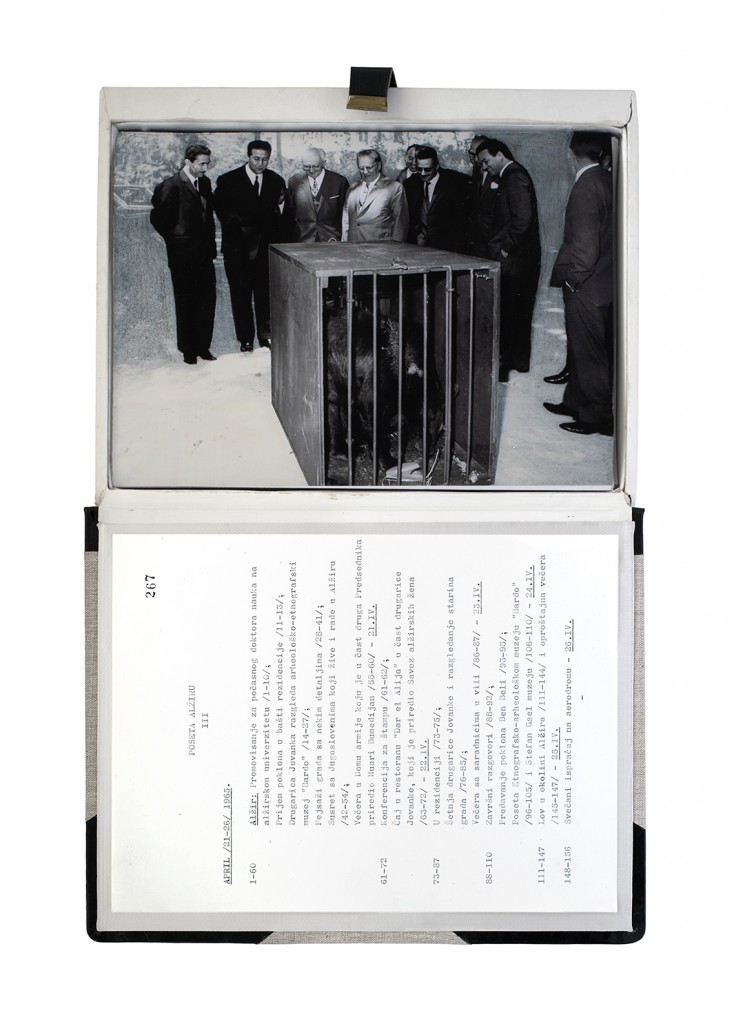

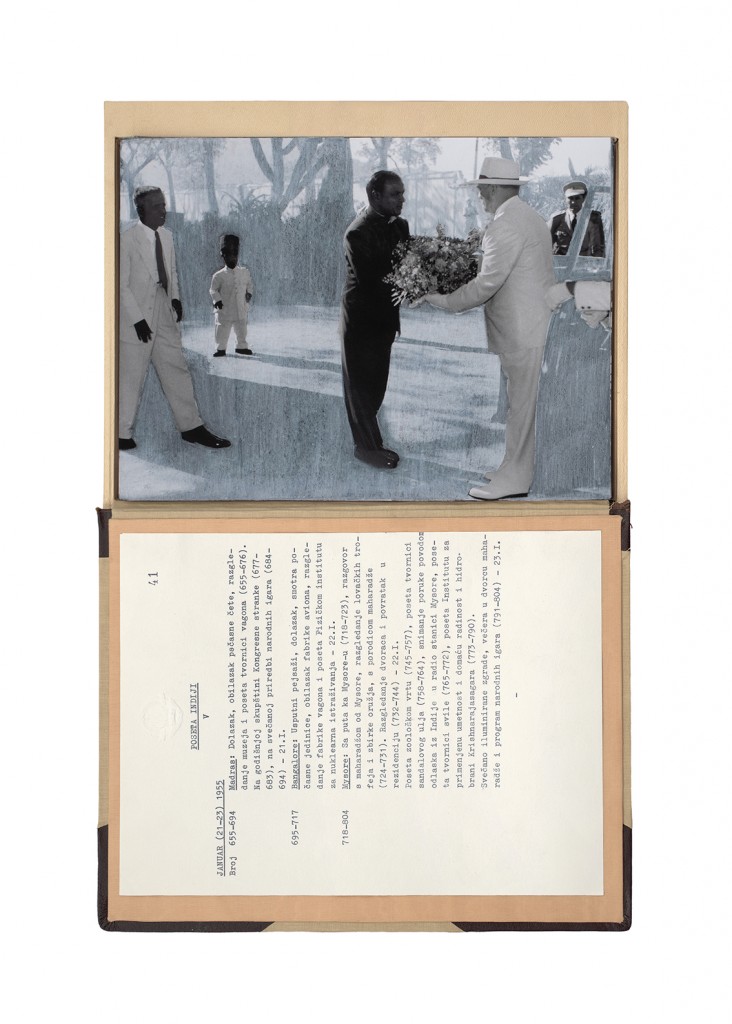

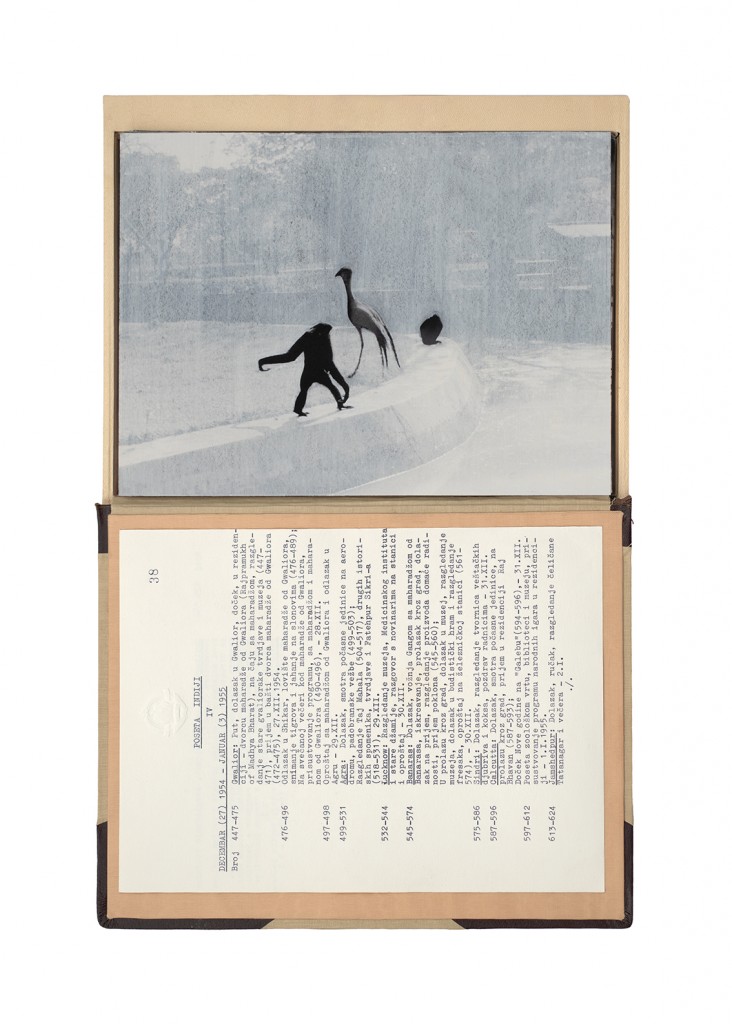

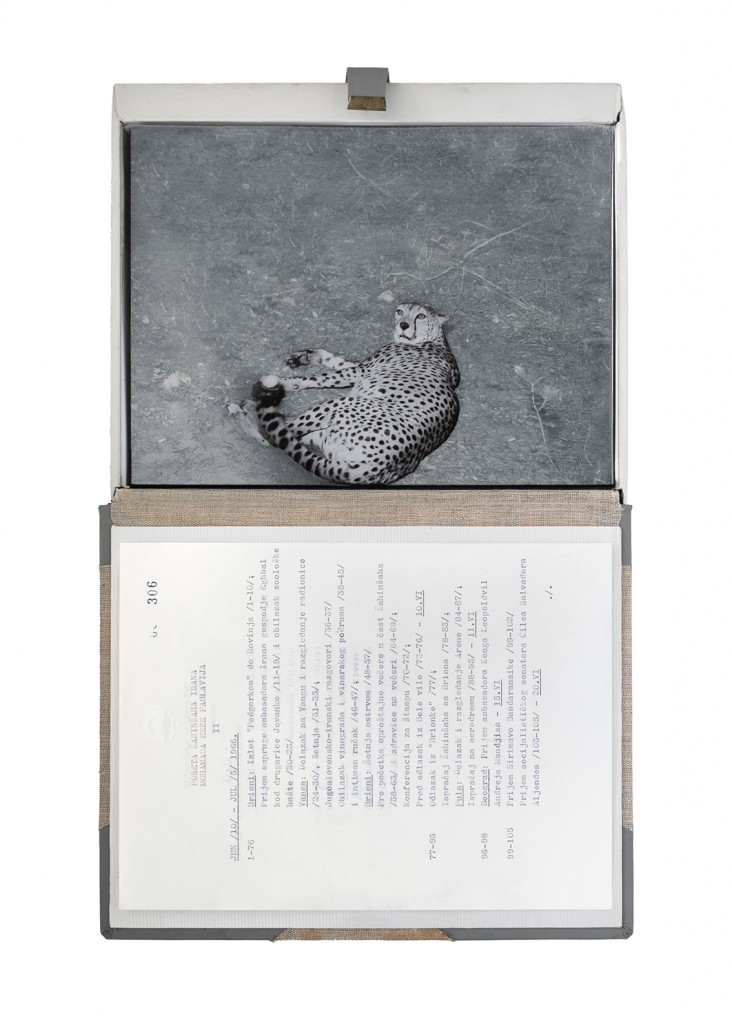

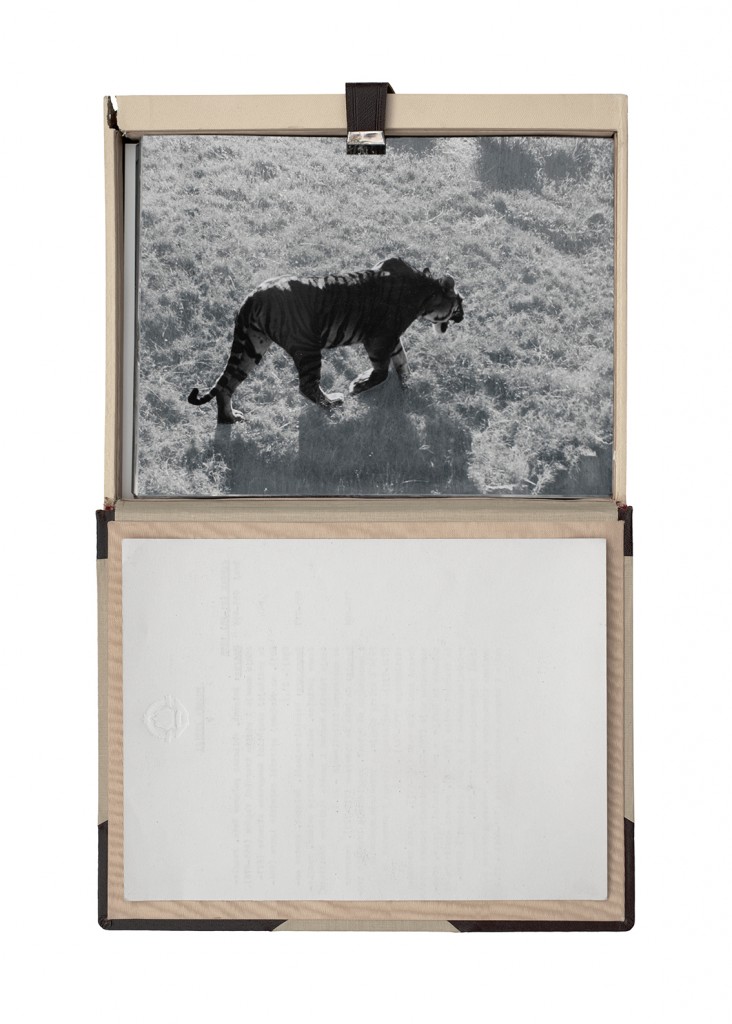

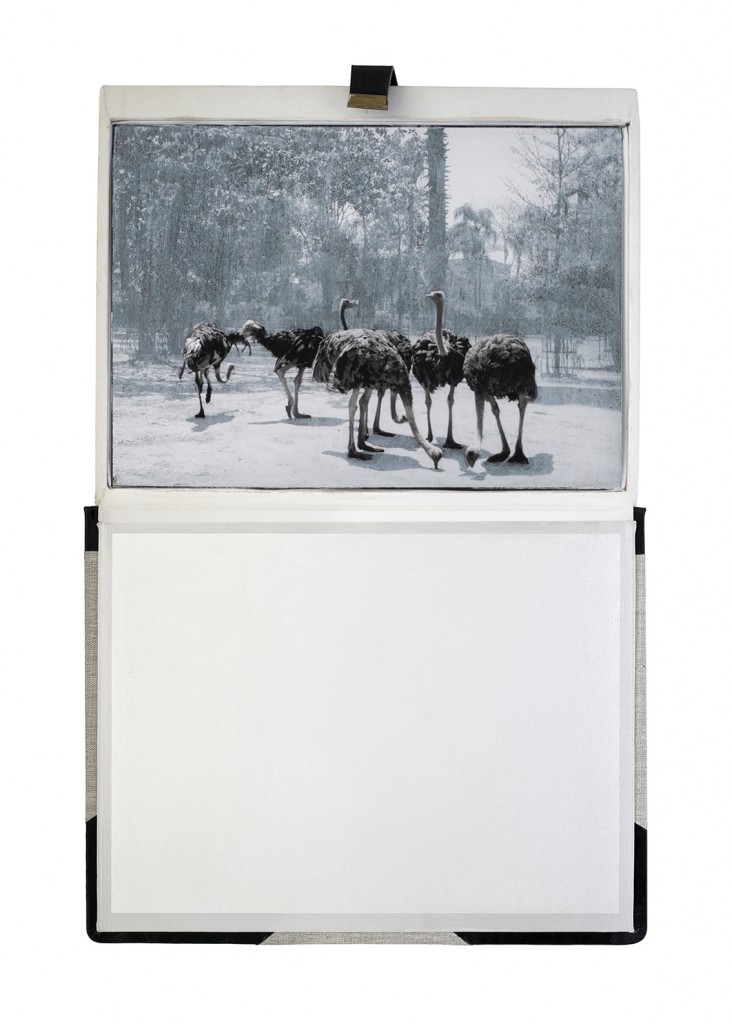

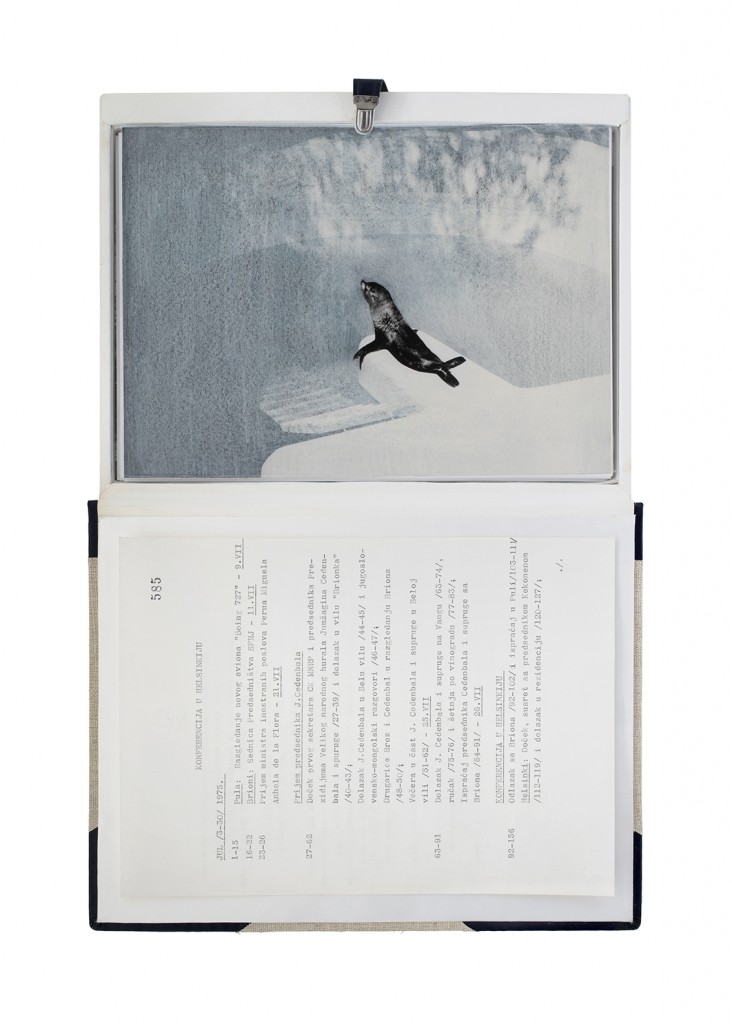

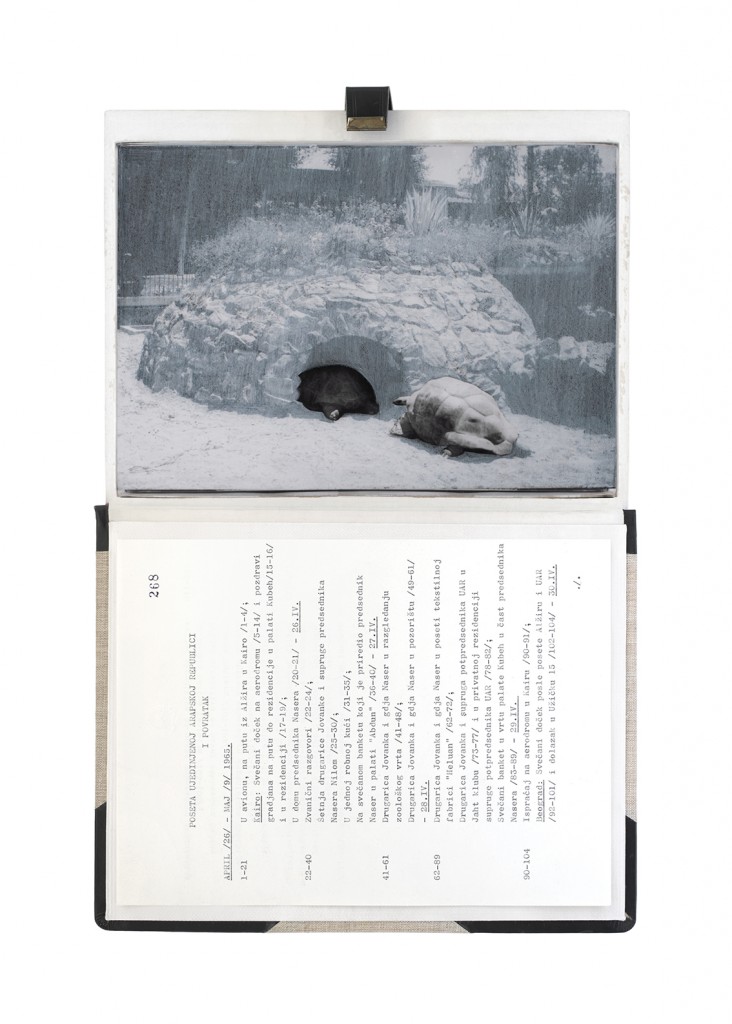

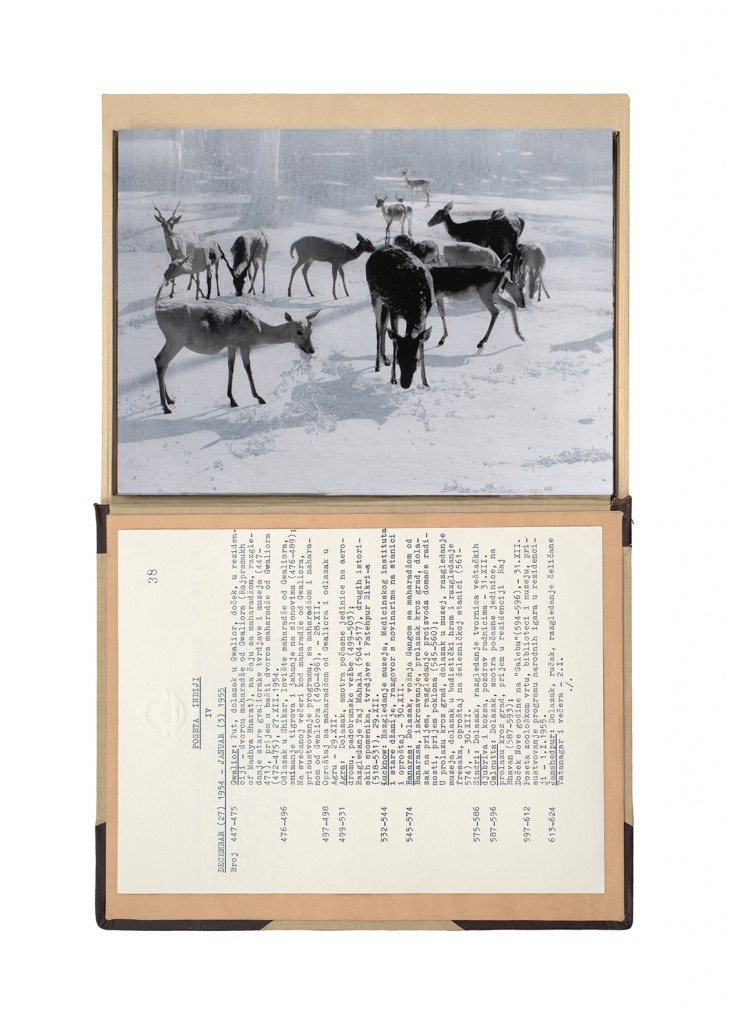

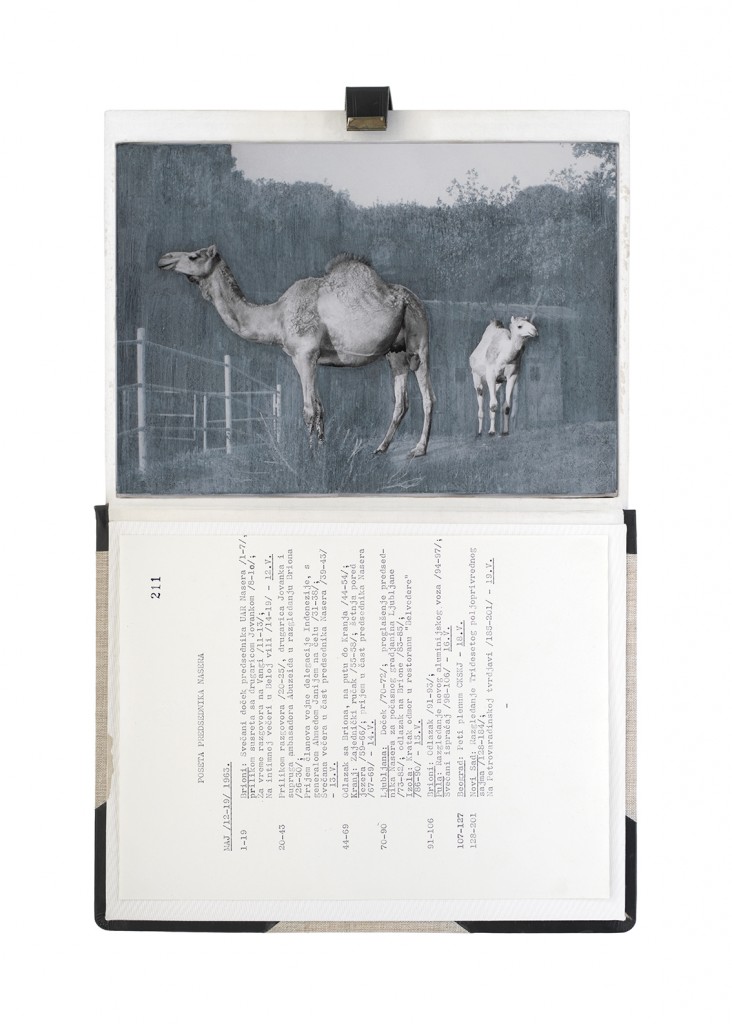

Socialist Yugoslavia, which aligned itself through the United Nations and the Non-Aligned Movement with the recently decolonised countries of the so-called Third World, materialised its diplomatic strategies through a menagerie of animals—tokens of international connection, gathered during President Josip Broz Tito’s maritime expeditions to Asia and Africa. These animals were collected, utilised, and understood in ways intimately tied to the embodied political practices of the Cold War, helping to craft a vision of Yugoslavia’s political territory and geopolitical ambition.

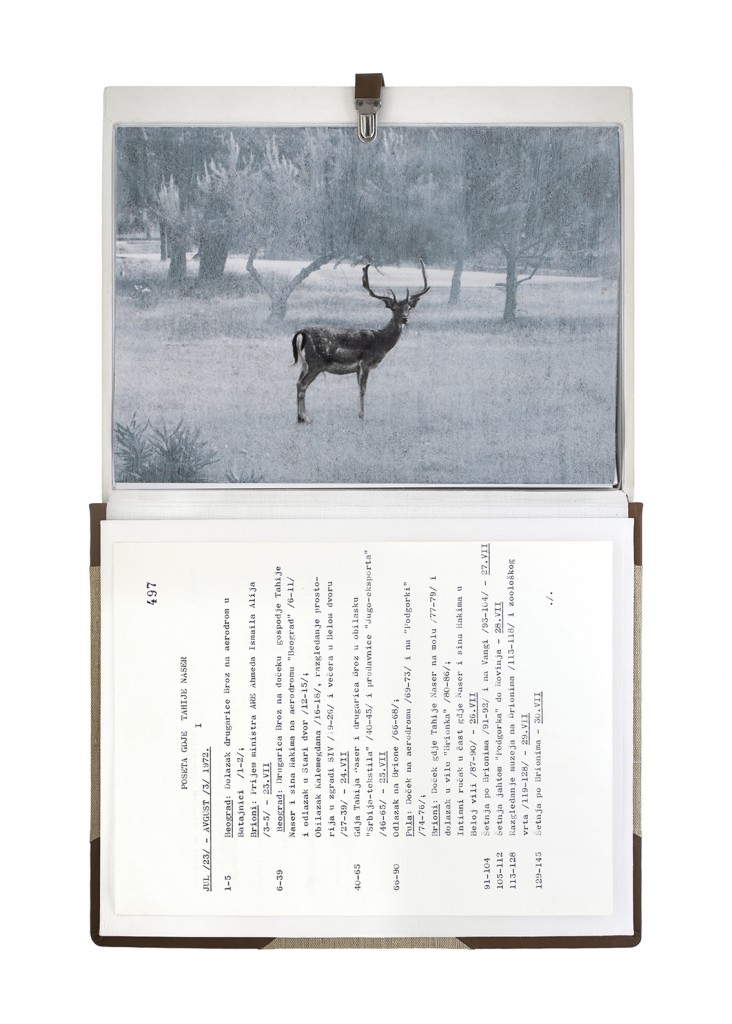

Yugoslavia’s Brioni island became both a host organism and a replica of the non-aligned world, a geographic imaginary of international politics. Beyond symbolising transnational solidarity, the island functioned as a site of Yugoslav statecraft and stagecraft: a stage within a stage where international hierarchies were performed and power relationships negotiated. The case study of the Brioni Island zoo reveals a utopian diplomatic project with worldbuilding potential—one seemingly spared from the colonial aspirations and dominion of the Global North. As such, the Brioni zoo “was not merely a projection of power but a representation of a failed utopia in the making” (Tijana Vuješević, On Animals and Seas: Menageries as Representations of Yugoslav Global and Local Space in the Cold War Era).

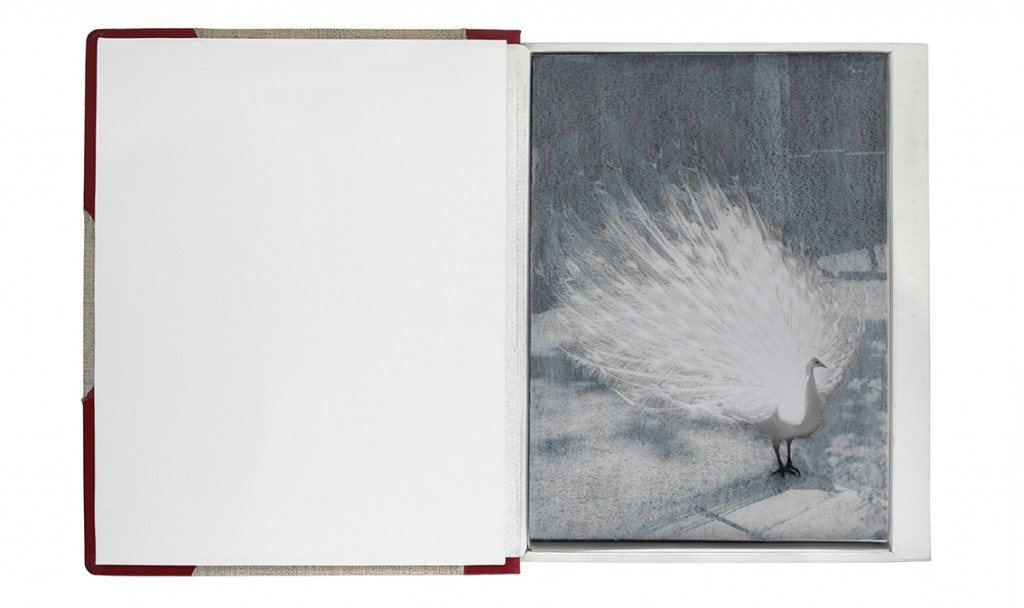

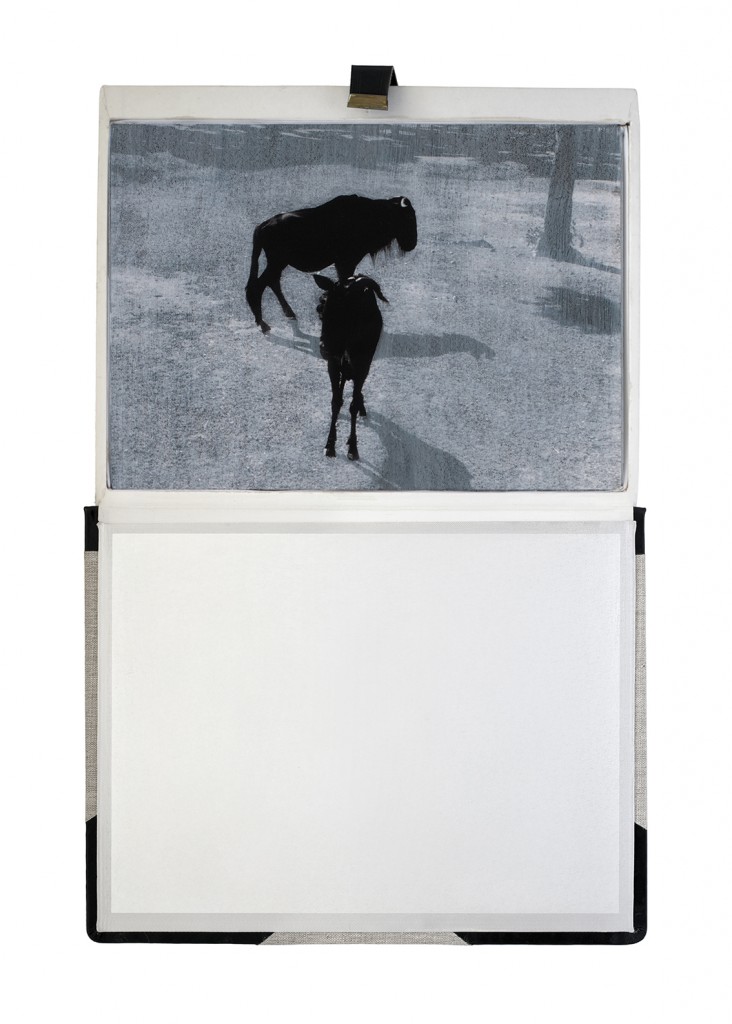

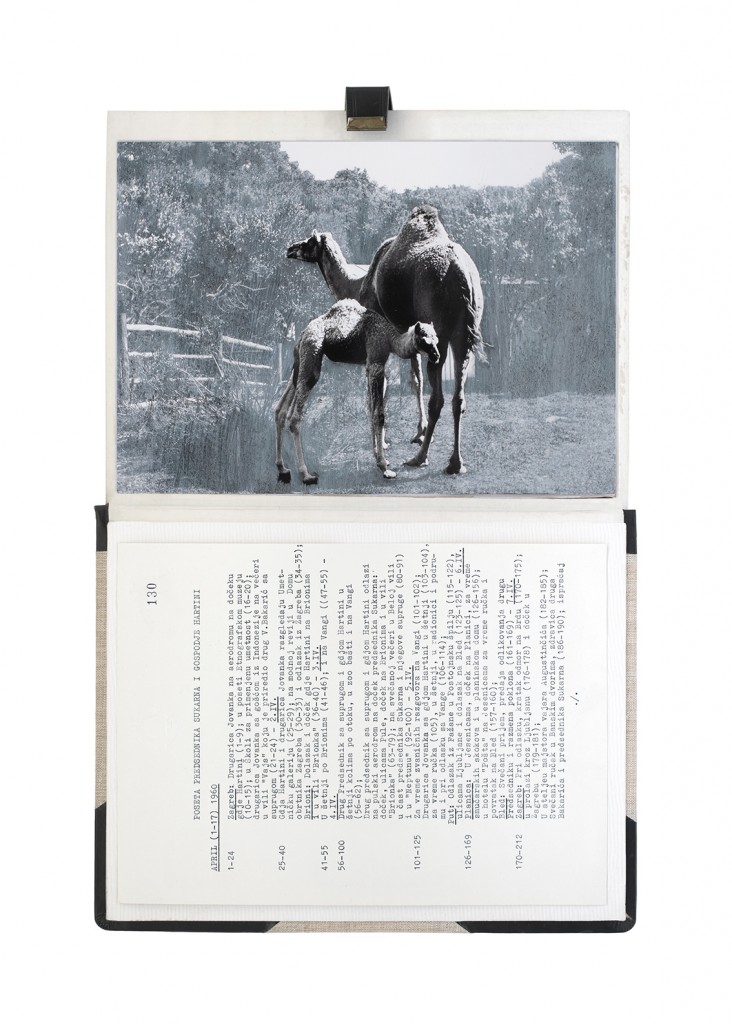

The Gift Ecology presents a series of photographs of Yugoslav government documents detailing the exchange of animals and the ritual functions these gifts performed symbolically in constructing a new transnational political space. Jasmina Cibic erases the geographical context surrounding the events, focusing the viewer’s attention instead on the animals’ portraits and the diplomatic viewership their display once served. As many of the countries—and the multilateral alignments these animals were tasked to represent—begin to fracture or dissolve, the animals’ role as gifts becomes untethered from the obligation of reciprocity. This frees the contemporary viewer to consider their transformed identities, shaped by shifting power structures and silences—perhaps destined to remain forever backstage, within the liberated ruins of colonial and ideological structures.

The Gift Ecology challenges us to see animals not only as silent observers but active agents in the field of politics and international relations – as an archive of soft power and its historical extractivist methods.